Importance: Gossip, defined by social scientists as “evaluative talk about an absent third party,” is anecdotally pervasive, yet poorly understood in surgical residency programs.

Objective: This study sought to deconstruct the role of gossip in surgical residency and evaluate its impact through the lens of surgical residents.

Design: In this qualitative study, semi-structured interviews were conducted with general surgery residents.

Setting: Interviews were conducted from July 2, 2023, to October 5, 2023 via Zoom™ videoconferencing.

Participants: Thirty-six residents from nine surgical training programs across the United States were interviewed.

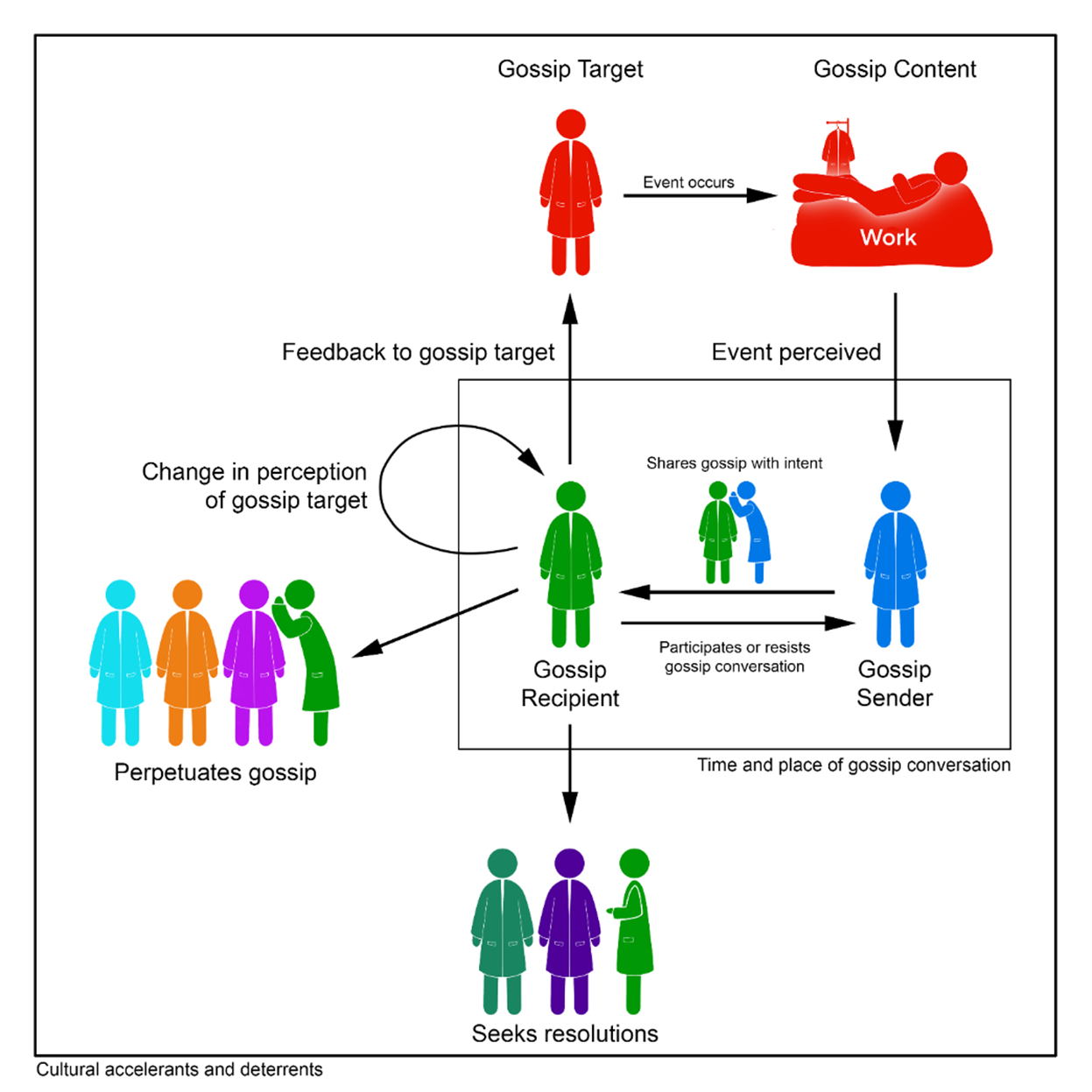

Main outcomes and measures: A thematic analysis using a grounded theory approach was conducted, and a process model was developed to represent study findings.

Results: Seven themes were developed: 1) The definition of gossip is elusive yet can include both positive and negative connotations; 2) Gossip contributes durably to one’s reputation within a program; 3) Gossip can be used as a form of instruction; 4) Gossip flourishes in environments without transparency and among those experiencing burnout; 5) Gossiping across a hierarchy may force those lower on the hierarchy into uncomfortable situations; 6) Remaining mindful of gossip’s potential impact can improve culture; and 7) Gossip can build or destroy trust.

Conclusions and relevance: Gossip is a complex social phenomenon with the potential to harm or help surgical residents. Rather than trying to eliminate gossip, programs should encourage the known positive impacts of gossip by increasing transparency, enhancing resident wellness, building awareness of existing hierarchies, and improving resident emotional intelligence.

Introduction

Gossip, defined by social scientists as “evaluative talk about an absent third party,” is pervasive in society (1, 2). A 2019 study randomly sampled audio segments from the conversations of over 450 people during a three-day period and found that they spent 52 minutes per day gossiping on average (3). Others estimated gossip to be even more prevalent in daily interactions (4, 5). In fact, anthropologist Dunbar stated, “Gossip is what makes society as we know it” (6). While the intentions behind gossip vary, these conversations build and maintain the social networks that make us human (7).

Gossip has yet to be empirically studied in general surgery training programs. Redelmeier et al. illustrated both positive (e.g., maintains a sense of belonging and inclusion) and negative (e.g., propagates harmful misinformation) impacts of gossip within a general hospital setting (8). Thomas & Rozell described positive and negative effects of gossip on nurses and potential downstream impacts on patient care (9). Ultimately, Chaikof et al. calls for acceptance of gossip as a normal part of interpersonal healthcare dynamics and highlights the importance of further study (10). General surgery residents frequently face high-stakes clinical situations, which mandate communication with patients, families, attending surgeons, nursing staff, and each other (11, 12). Given this high frequency of interpersonal interactions, gossip not only occurs in, but likely affects the surgical learning environment. Large survey-based studies demonstrate that surgery residents suffer from burnout at alarming rates, which is impacted by communication and organizational culture (13, 14). Calls for wellness initiatives in surgery training programs could be informed by an analysis of the social interactions—including gossip— which residents experience on a daily basis (15).

In this study, we sought to explore gossip in surgical residency through semi-structured interviews with residents across the U.S. The primary aims were to 1) construct a process model for how and why gossip occurs in general surgery residency programs, 2) uncover the positive and negative impacts of gossip, and 3) determine how to enhance the benefits of gossip while curtailing its drawbacks.

Methods

This project was deemed exempt from full review by the Institutional Review Board. This study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines (Appendix A) (16, 17).

Participants

Author JCL invited members of the Collaboration of Surgical Education Fellows (CoSEF), a multi-institutional, resident-led group of surgical education fellows, to join this initiative (18). Collaborators recruited four participants from their institution through purposive sampling. All categorical general surgery residents at their institutions met inclusion criteria. Author JCL conducted all interviews. Due to the sensitive nature of these interviews, no participants from JCL’s home institution were included. The interviewer emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary, and responses would be deidentified. Participants consented to participate verbally prior to their interview.

Semi-Structured Interviews

Authors JCL & BAAW created a semi-structured interview guide using an attributional process model of workplace gossip as a framework (Appendix B). This theory posits that people contextualize gossip by considering both internal (e.g., personality attributes) versus external (e.g., situational attributes) factors (19). JCL piloted the interview guide iteratively with CoSEF members. First, participants described their definition of gossip before the interviewer provided the academic definition (“evaluative talk about an absent third party”) to establish a consistent, shared understanding for the remainder of each interview (1, 2). The interviewer then asked participants for instances of gossip that they had recently heard and shared with others and prompted exploration of intent, purpose, and impact for each instance. Interviews occurred from July 2, 2023, to October 5, 2023 via Zoom™ videoconferencing, which lasted 15-30 minutes. Only author JCL and the participant were present for interviews. No participants were interviewed more than once. Each interview was transcribed using Zoom™. Collaborating authors each manually reviewed and anonymized transcripts from conversations who were not from their own institution. Participants were provided their anonymized transcript and given the opportunity to provide clarifications or redactions.

Analytic Approach

We conducted a reflexive thematic analysis of transcripts using a grounded theory approach (20, 21, 22). First, authors JCL and BAAW read four transcripts independently to gain familiarity with the data. These two authors met to discuss patterns and develop an initial codebook based on the attributional process model of workplace gossip (19). After both authors independently coded the first four interviews, it became clear that many recurring concepts were not captured by this initial approach. Therefore, coders moved to open coding. They met again to discuss codes and consolidate a final codebook. Once authors JCL and BAAW agreed on code definitions, they divided the transcripts and coded them independently using the finalized 48-item codebook (Table 1) (23). After coding was complete, all authors met to construct themes via collaborative discussion. Study participants were provided with the final themes and given an opportunity to comment. In order to establish trustworthiness, researchers engaged with the data over nine months, participated in peer debriefing, and vetted themes as a team (24). Coding was organized using Microsoft Excel (Version 2312, Redmond, WA, USA, 2021).

Reflexivity

The first author and solo interviewer (JCL) is a male general surgery resident with an MD who holds an undergraduate degree in Psychology. During the study period, he was pursuing a Master of Health Professions Education with coursework in and had prior experiences using qualitative methods (25). He regularly engaged in feedback sessions with author BAAW regarding his interview techniques. To promote honesty and vulnerability given the sensitive nature of gossip, he emphasized confidentiality prior to each interview. During each interview, he documented his own reflections.

Authors JCL and BAAW performed transcript coding. BAAW is a female Associate Professor of Health Professions Education with an EdD and MA whose career has focused on teams in medicine. She teaches qualitative methodology courses to Masters and Doctoral students. As a non-surgeon, she carried fewer preconceptions about gossip among surgical residents, which provided a different lens through which to carry out thematic analysis. The remainder of the study team included a gender-diverse group of clinical general surgery residents ranging from PGY-1 through PGY-6 from nine institutions across the U.S. who were able to contextualize participant stories through their own experiences.

Results

Participant Demographics

Thirty-six general surgery residents participated in interviews (Table 2). Nine academic training programs were represented across each U.S. geographic region (Northeast=1; Midwest=2; South=2; West=4). The mean participant age was 30.5 years. Twenty-five were females (69%). Twenty-six were white (72%). While each post-graduate year was represented, the majority were senior (PGY 3-5) residents (87%).

Gossip Process Model

Forty-eight codes were organized into six categories and eleven subcategories (Table 1), which were used to construct a process model describing how gossip occurs in surgical residency (Figure 1). First, a gossip sender observes an event (e.g., poor performance on a task) involving the gossip target (e.g., co-residents, attendings). The gossip sender, with a specific motive (e.g., to make meaning out of a situation), describes this event to the gossip recipient at a particular time and place (e.g., at shift change). The gossip recipient participates in or resists the gossip conversation. The recipient can then perform several actions: 1) do nothing; 2) seek resolutions to the situation; 3) perpetuate the gossip; or 4) give feedback to, support, or condemn the gossip target directly. They also may or may not change their perception of the gossip target or sender. Program culture (e.g., transparency, hierarchy) influences each step of this process.

Overarching Themes

1. The definition of gossip is elusive yet can include both positive and negative connotations. Although most participants defined gossip as negative talk, several gave examples of gossip as positive talk: “I gossip about people in a positive way. I'm frequently like, “Oh, my gosh. This person [is] so cool. I did this case with her, and she's so smart . . . You want to do cases with her.” (P22) Because of the negative connotation of gossip in popular culture, some participants did not consider negative content with positive intent as gossip, blurring the lines between “positive” and “negative” gossip: “If someone had a negative experience with the individual [and wanted to discuss it], I don't see that as gossip, because they’re trying to talk through a problem with a friend.” (P14)

2. Gossip contributes durably to one’s reputation within a program. Typically, participants described the potential for negative reputations to develop early in residency: “Once you establish a reputation with the faculty, it sticks, and it's really hard to shake. There are some specific examples of residents who didn't get off on the right foot when they started as interns, but really turned things around. But, they get treated a little differently.” (P23)

3. Gossip can be used as a form of instruction. Informal conversations about others’ mistakes can be used as learning opportunities, although the lesson may be incomplete: “[Gossip is] like M&M. It's really helpful for us . . . you hear about these negative things that have happened in the past and it does make you more aware of the pitfalls that you could run into. But... with gossip, the person who actually made the mistake doesn't get to actually share what they learned from it, which is probably the most important piece of it all.” (P6)

4. Gossip flourishes in environments that lack transparency and among those experiencing burnout. When decisions are made without explanation to those directly impacted, gossip inevitably occurs, especially when people feel overworked: “[I was on a team with a co-resident] who got pulled out of clinical rotation. . . No one got an explanation. Of course we're all a little bit peeved because it sucks to have your schedules changed last minute, especially getting pulled to cover the worst rotations, losing days off, and in some cases … almost… violating duty hours. Almost instantaneously, people identified . . . this resident . . . and people were making up whatever stories [about their absence that] made sense.” (P13)

5. Gossiping across a hierarchy may force those lower on the hierarchy into uncomfortable situations. Some residents described feeling unable to stand up to gossip from attendings: “There's such a power dynamic between attending staff, fellows, residents… if I were in another setting I would have said ‘that's not professional.’ But it doesn't really feel like you can say that in surgery to your attending.” (P29). Furthermore, sharing gossip about a superior’s performance may influence power dynamics: “It will be me and a medical student, and [an attending] would ask me about the [junior residents] . . . how they’re doing. It was well intentioned, but if I were the medical student, I’d feel kind of awkward. If I were the intern, I don't know that I would want the medical student knowing my deficiencies necessarily.” (P21)

6. Remaining mindful of gossip’s potential impact can improve culture. Appreciating the complexity of situations and assessing the potential impact on others as a gossip sender and recipient can mitigate negative effects: “[Every] story has two sides. When I am both hearing and sharing gossip, I try to keep in mind how the individual that's being talked about would respond to the situation again. Would they feel comfortable in this [conversation]? And then I try to react accordingly.” (P25)

7. Gossip can build or destroy trust. Sharing gossip with others can signal to the recipient that they are worthy of being trusted with information: “He must trust me or must see me as a friend, because he's willing to share this gossip with me and is willing to let me in [on the gossip]. It made me feel like I had a bond with him.” (P27) When hearing gossip from a superior, the gossip recipient may view this as a breach of power and perceive them as untrustworthy: “It's one thing I think, for somebody who's your peer to share things with you. I think it's something entirely different when somebody who's in a position of power shares something like that with you, especially something that the resident I'm sure told [this attending] in [confidence]. [This] made me think twice about sharing things with that [attending].” (P11)

Discussion

Through qualitative semi-structured interviews, we rigorously deconstructed gossip in surgical residency. We built a process model for gossip in surgical residency and described seven overarching themes. These results provide a better understanding of the training environment and insight into improving the gossip culture. Gossip is innate to any place where humans work together; it cannot be removed or destroyed (5). While the content of the gossip may be positive or negative in valence, the intentionality of sharing the message is much more critical (26). For example, sharing that a resident is struggling and in need of peer support is negative gossip. However, if sharing this information with others is intended to or solicits peer support, the outcome is positive. Participants emphasized the importance of promoting gossip that can bring about positive change (pro-social) and decreasing hurtful, harmful, and unproductive gossip (anti-social). We have identified several ways to achieve this objective at the institutional and individual level.

Culturally driven elements of an institution including transparency and burnout influence gossip. Surgery residents highlight that gossip occurs when the truth is withheld. Good surgical leadership includes transparent communication (27). Often formal transparency involves sharing information after decisions have already been made whereas gossip circulates in real time (28). Informal gossip democratizes information, thereby making it more available to the general population (29). Real-time transparency from the department level may reduce unnecessary gossip by providing truth. Many situations (e.g., a resident struggling) require a balance between transparency and privacy. In an argument for transparency, residents expressed that knowing the reason for sudden schedule changes to cover for a co-resident improves willingness to help. Additionally, through gossip, residents will likely find out regardless of efforts from the program to hide this information. When matters of a struggling resident will impact others directly, discussing a situation dissemination plan with the struggling resident may reduce factually incorrect and anti-social gossip. Nevertheless, residents must maintain their right to privacy should they want it. In addition to encouraging transparency, addressing burnout will likely decrease anti-social gossip. Burnout—a complex syndrome of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization—runs rampant amongst general surgery residents (30). In the hospital setting, anti-social gossip is associated with burnout (31). Improving resident wellness through multilevel approaches may decrease anti-social gossip (15, 32).

Gossip, power, and hierarchy are interconnected. In this study, surgery residents described knowing and using gossip as social capital that influences one’s power within the program. Undeniably, gossip can be weaponized; information about others can be selectively shared to negatively impact rivals’ reputations (33). However, high-frequency gossipers may be perceived as less powerful and less well liked by peers (34). Those who do not know any gossip may have been marginalized from a group and hold little social capital, whereas those who gossip regularly may be viewed as untrustworthy (2, 34). Selectively sharing gossip maximizes power (34). Notably, the status differential between the gossiper and recipient impacts gossip. Social exchange theory suggests that people gossip upward (with their superiors) to exert influence and gain resources from the person in higher power, while they gossip laterally (with their peers) for social support. Social scientists posit that downward gossip (with subordinates) may be less common because subordinates do not have useful social resources to offer (35). Nevertheless, hearing gossip from a superior may increase feelings of well-being, belonging, and empowerment according to commitment theory (36, 37). Ultimately, hearing gossip—particularly negative comments about a friend—from across a hierarchical differential can be uncomfortable and may damage relationships (38). In this study, residents are divided; some felt that gossiping with people higher on the hierarchy was a positive experience, while others described feeling coerced to participate in gossip with their supervisors. This difference in experiences likely depended on the gossip content and the gossip receiver’s relationship with the gossip target and the gossiper. While senior residents should consider sharing lighthearted gossip with their juniors to foster inclusion, they should avoid sharing sensitive information or gossip about a junior’s peers with them.

At the individual level, mindfulness and emotional intelligence are critical to reducing anti-social gossip. Mindfulness (being present in the moment to become less reactive and more responsive (39)) and emotional intelligence (having insight into yourself and others to more effectively manage your behavior and relationships (40)) center around emotional perception and considerate action. Both skills can be taught to surgical residents (12, 41). Rahmani produced a useful model for responding to anti-social gossip that invokes these concepts: initially, remain indifferent and do not propagate; second, consider the impacts of sharing this information from a variety of perspectives; third, weigh the pros and cons of taking action; finally, craft the appropriate action plan (42). The gossip process model developed in this study similarly describes the potential actions that a gossip recipient can take. Using discretion, seeking resolutions, and providing feedback to gossip targets are most likely to have a positive impact.

This study has key limitations. First, despite the diverse participant pool, there may be relevant concepts that were not well represented in these interviews. Second, residents more prone to gossip may have been more likely to agree to participate, and therefore may be overrepresented. However, the intent of this work was to develop a better understanding of the phenomenon rather than quantitatively describe gossip among surgical residents. Third, this study involved only general surgery residents; different specialties have different cultures and may therefore experience gossip differently (43). Finally, while residents gossip, their perspectives do not provide a complete story. Future work from our group aims to capture the attending surgeon perspective on gossip in surgical training programs.

Conclusion

Gossip is a complex social phenomenon that can harm or help surgical residents. Gossip cannot be removed from surgical training. Instead, programs should increase transparency, enhance resident wellness, build awareness of existing hierarchies, and improve resident emotional intelligence to encourage the known positive impacts of gossip.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Irene Yu for her artistic representation of the gossip process model.

References

- Eder D, Enke JL. The Structure of Gossip: Opportunities and Constraints on Collective Expression among Adolescents. American Sociological Review. 1991;56(4):494-508.

- Foster EK. Research on Gossip: Taxonomy, Methods, and Future Directions. Review of General Psychology. 2004;8(2):78-99.

- Robbins ML, Karan A. Who Gossips and How in Everyday Life? Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2019;11(2):185-95.

- Emler N. Gossip, reputation, and social adaptation. Good gossip: University Press of Kansas; 1994. p. 117-38.

- Dunbar RIM, Marriott A, Duncan NDC. Human conversational behavior. Human Nature. 1997;8(3):231-46.

- Dunbar RIM. Gossip in Evolutionary Perspective. Review of General Psychology. 2004;8(2):100-10.

- Beersma B, Van Kleef GA. Why people gossip: An empirical analysis of social motives, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2012;42(11):2640-70.

- Redelmeier DA, Etchells EE, Najeeb U. Principles and Practice of Gossiping About Colleagues in Medicine. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2021;16(12):763-6.

- Thomas SA, Rozell EJ. Gossip and Nurses: Malady or Remedy? The Health Care Manager. 2007;26(2).

- Chaikof M, Tannenbaum E, Mathur S, Bodley J, Farrugia M. Approaching Gossip and Rumor in Medical Education. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(2):239-40.

- Nakagawa S, Fischkoff K, Berlin A, Arnell TD, Blinderman CD. Communication Skills Training for General Surgery Residents. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(5):1223-30.

- White BAA, Fleshman JW, Picchioni A, Hammonds KP, Gentry L, Bird ET, et al. Using an Educational Intervention to Map our Surgical Teams' Function, Emotional Intelligence, Communication and Conflict Styles. J Surg Educ. 2023;80(9):1277-86.

- Ellis RJ, Nicolas JD, Cheung E, Zhang L, Ma M, Turner P, et al. Comprehensive Characterization of the General Surgery Residency Learning Environment and the Association With Resident Burnout. Ann Surg. 2021;274(1):6-11.

- Lund S, D'Angelo AL, Busch R, Friberg R, D'Angelo J. With a Little Help From My Friends: The Negating Impact of Social Community and Mentorship on Burnout. J Surg Res. 2022;278:190-5.

- Anand A, Jensen R, Korndorffer JR, Jr. We Need to Do Better: A Scoping Review of Wellness Programs In Surgery Residency. J Surg Educ. 2023;80(11):1618-40.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-57.

- Dossett LA, Kaji AH, Cochran A. SRQR and COREQ Reporting Guidelines for Qualitative Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(9):875-6.

- Kratzke IM, Lund S, Collings AT, Doster DL, Clanahan JM, Williamson AJH, et al. A novel approach for the advancement of surgical education: the collaboration of surgical education fellows (CoSEF). Global Surgical Education - Journal of the Association for Surgical Education. 2022;1(1):38.

- Lee SH, Barnes CM. An attributional process model of workplace gossip. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(2):300-16.

- Chapman AL, Hadfield M, Chapman CJ. Qualitative research in healthcare: an introduction to grounded theory using thematic analysis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(3):201-5.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide: SAGE Publications; 2021.

- Sandhu G, Kaji AH, Cochran A. Practical Guide to Qualitative Research in Surgical Education. JAMA Surg. 2024.

- Creswell JW, Báez JC. 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher: SAGE Publications; 2020.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2017;16(1):1609406917733847.

- L’Huillier JC, Jensen RM, Clanahan JM, Lund S, Myneni AA, Noyes K, et al. The surgical education research fellowship: a qualitative analysis of recent graduates’ perceptions. Global Surgical Education - Journal of the Association for Surgical Education. 2023;2(1):103.

- Testori M, Dores Cruz TD, Beersma B. Punishing or praising gossipers: How people interpret the motives driving negative gossip shapes its consequences. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2023:No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified.

- Kane RL, Egan JM, Chung KC. Leadership in Times of Crisis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(4):899-906.

- Sobering K. Watercooler Democracy: Rumors and Transparency in a Cooperative Workplace. Work and Occupations. 2019;46(4):411-40.

- Fung A. Infotopia: Unleashing the Democratic Power of Transparency*. Politics & Society. 2013;41(2):183-212.

- Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Ascher NL, O'Sullivan PS, Harris HW, Epel ES. Burnout and Stress Among US Surgery Residents: Psychological Distress and Resilience. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2018;226(1):80-90.

- Georganta K, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A. Talking behind their backs: Negative gossip and burnout in Hospitals. Burnout Research. 2014;1(2):76-81.

- Golisch KB, Sanders JM, Rzhetsky A, Tatebe LC. Addressing Surgeon Burnout Through a Multi-level Approach: A National Call to Action. Curr Trauma Rep. 2023;9(2):28-39.

- McAndrew FT, Bell EK, Garcia CM. Who do we tell and whom do we tell on? Gossip as a strategy for status enhancement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2007;37(7):1562-77.

- Farley SD. Is gossip power? The inverse relationships between gossip, power, and likability. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;41(5):574-9.

- Martinescu E, Janssen O, Nijstad BA. Gossip as a resource: How and why power relationships shape gossip behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2019;153:89-102.

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review. 1991;1(1):61-89.

- Chang K, Kuo C-C. Can subordinates benefit from Manager’s gossip? European Management Journal. 2021;39(4):497-507.

- R K. Managing Conflicts, How to work for a gossipy boss 2017 [Available from: https://hbr.org/2017/01/how-to-work-for-a-gossipy-boss.

- Stephen AE, Mehta DH. Mindfulness in Surgery. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13(6):552-5.

- White BAA, Quinn JF. Personal Growth and Emotional Intelligence: Foundational Skills for the Leader. Clin Sports Med. 2023;42(2):261-7.

- Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Olaru M, Sugrue LP, Staffaroni AM, Delucchi KL, et al. Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Training in Surgery: Additional Analysis of the Mindful Surgeon Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194108.

- Rahmani M. Helping Program Directors Effectively Manage Rumors and Gossip. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2018;10(6):616-9.

- Bisgaard EK, Moore MK, Stadeli KM, Champan CY, Sanapoori SH, Lobova VA, et al. Defining the Culture of Surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2023;237(2).

Table 1:

| Code | Subcodes | Description | Sample Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| What? | |||

| Definition of gossip | Positive | Gossip is about positive topics exclusively | “I gossip about people in a positive way. I'm frequently like, “Oh, my gosh. This person [is] so cool. I did this case with her, and she's so smart . . . You want to do cases with her.” (P22) |

| Negative | Gossip is about negative topics exclusively | “I think of gossip as something that's pretty hurtful.” (P19) | |

| Both/Neutral | Gossip can be about negative or positive topics | “Like getting together with your girlfriends over coffee, and chatting about some of the funny, silly events that have gone on. I think my very first response is not necessarily negative and more benign and silly.” (P6) | |

| Content of gossip | Unreliable or lazy colleagues | Coworkers not following through with tasks, not working hard, or poor teamwork | “[For example,] this PGY2 took her 400th sick day this year. How does someone have COVID that many times?” (P16) |

| Performance | Ability to perform required tasks or skill progression through training | “How [a junior resident is] performing in the program. Whether or not they were progressing as appropriate.” (P4) | |

| Admirable behavior | Behaviors that are worth promoting | “I've encountered some superstar interns . . . I've told people when they're going to their team. ‘You're going to have a great team member. You'll be able to relax and kind of let them run the floor.” (P31) | |

| Faculty who are good or bad to work with | Experiences with and attributes of faculty that make working with them a positive or negative experience | “There's a lot to learn from [an attending] technically, but just in terms of interpersonal dynamics, [they’re] really challenging to work with. A lot of the support staff don't enjoy working with this person.” (P29) | |

| Interpersonal relationships | Non-professional relationships between people | “It was like this extra-marital affair, and basically kind of blew up his life.” (P5) | |

| Changes in roles, responsibilities, tasks | Discussion about new leadership, faculty, or changing responsibilities | “Did you hear that [an attending] is taking a new job elsewhere?” (P16) | |

| Who? | |||

| Who gossips | Friends | Gossip between two friends at a similar hierarchical level | “I feel like when [gossip] happens, it's always me talking to other residents. I don't really talk to leadership about this kind of stuff.” (P2) |

| Resident-supervisor pairs | Gossip between two people at different hierarchical levels | “I was talking with an attending, and she was telling me about one of her [former] coresidents.” (P5) | |

| Significant others | Gossip between two people in a romantic relationship | “Sometimes I'll mention [gossip] to my husband if he asks about my day.” (P20) | |

| Gossip targets | Co-residents | Gossip about co-residents | “[Our class] has been hearing that other years have been talking about us and the way our [notes] are written and things like that.” (P7) |

| Attendings | Gossip about program faculty/attendings | “Someone told me yesterday about an attending that did something that seemed questionable in the OR.” (P22) | |

| Medical students | Gossip about medical students | “When we talk about medical students, we're often extremely judgmental, because we're assessing them for their potential as part of our residency.” (P20) | |

| Other staff | Gossip about nurses, Advanced Practice Providers, OR staff, other members of the healthcare team | “There's the category of nurses who you're worried about taking care of your sick patient, and there's a category of nurses who you just roll your eyes at, because you know you're going to get paged a lot that night.” (P23) | |

| The program | Gossip about the residency program at large | “Our program tends to be very insular in some sense . . . there has been some tension with trying to take ideas from other places. So that's one example of gossip” (P2). | |

| When? | |||

| Timing of gossip | Shift change/hand off | Gossip that occurs during hand offs in patient care | “There are definitely like sign outs and hand offs. As we switch rotations, you reach out to the person before you and talk about, “Oh you're going to have a great time with this senior. This senior is a little bit more tough to work with.” (P1) |

| Immediately after an event | Engaging in gossip immediately after an inciting event | “[After an event], I went to the call room, and one of my chiefs [was] there, and so I talked to him about it. So that was the first person I kind of spoke with about it.” (P26) | |

| Outside of work hours | Discussing gossip outside of work | “[Gossip happens] when that group of friends is hanging out socially.” (P4) | |

| Where? | |||

| Where gossip occurs | Workroom | Gossiping in resident workroom spaces | ‘Typically, [gossip happens] in the work room when that resident isn't present.” (P17) |

| Operating room | Gossiping in the operating room | “In the operating room, the attending was talking about one of my co-residents [that] she was very unhappy with . . . talking about it loudly with others in the room, and then also tried to involve me in the conversation.” (P35) | |

| Social gatherings | Gossiping at social gatherings outside of work | “We were no longer at work. We were just, you know, having a wine night and kind of gossiping about probably many things.” (P24) | |

| In passing | Gossiping in the hall, in the moment | “I had run into him in the hospital, and we were also pretty much just chatting.” (P9) | |

| Virtually | Gossiping that occurs with the use of technology, not face to face | “We have a group [text] chat.” (P34) | |

| Why? | |||

| Gossip intent | Make meaning out of situations | To understand a person or situation better | “We had a resident that quit . . . other people were talking about him leaving the program and the reasons he was leaving.” (P3) |

| Venting | To blow off steam | “I called one of my co-residents on the way to the hospital so I could yell about [a situation] to them, so I didn't yell at the nurse.” (P23) | |

| Heads up/warning | To warn against certain behaviors, upcoming issues, or events | “As an intern where everything feels new, if you can have some sort of tip of like, “Hey this attending likes things a certain way,” or “[an attending is] pretty frustrating [to work with].” [Gossip] was helpful and sort of protective in that sense.” (P27) | |

| Preparation | Seeking out information in advance of an experience | “Coming back to clinical [duties], I've been asking about like my incoming the class that I'm joining. How they perform clinically, so I know how much I can trust their sign out and their patient management. (P4) | |

| Comparing oneself to others | To compare your experience, success, or failure to another | “I’m comparing myself and others, and I'm comparing other residents to each other too. I guess it just sort of contextualizes my experience. It doesn't change it, but it's just probably human nature.” (P9) | |

| Increase social capital | To advance one’s standing in the program | “All information is asymmetrically shared and not often universally shared. That creates information hierarchy. And I do think that the information is a social currency in our field. People who have more of it usually informally, and maybe in some cases even formally, hold power over those who don't.” (P2) | |

| How? | |||

| Role in gossip | Active participant | Actively seek out or encourage gossip | “I'm going to have this piece of info, and I'm going to give it to everybody. And they're going to love this new update that I've got.” (P6) |

| Passive participant | Allow gossip to occur | “I'll allow conversations to go how they go.” (P14) | |

| Non-confrontational resister | Change the conversation topic or move away from gossip | “I don't think I would actively shut [gossip] down as much as just try to like steer the conversation in a different direction.” (P3) | |

| Reaction to gossip | Perpetuate gossip | Share it with others | “[One person] would literally come out of [residency review committee meetings] and just talk about it to people. He'd be like, ‘They think that this intern needs to be remediated.’ You can't be telling people about that.” (P16) |

| Seek solutions with others who are not involved in the gossip directly | Take action toward rectifying or preventing a situation with those who were not involved in the initial experience | “[I gossiped because] I was wanting her opinion on whether or not this [event] is reportable [to the program].” (P15) | |

| Seek solutions with others who are involved in the gossip directly | Take action toward rectifying or preventing a situation with those who were involved in the initial experience | “Person X is having a hard time in their relationship or really struggling on the wards. Someone really needs to pull them aside and be like, ‘Hey, are you doing okay?’ You know, have that check in.” (P26) | |

| No action | No action taken | “I just don't think that there was anything productive [to do about] that.” (P15) | |

| Change in perceptions of others | Perception of the gossip sender or gossip subject changes | “We're using gossip in a very like cancel culture type of way where it's like, “Oh, I heard that [a resident] is bad in the OR.’ And then it spreads, and then all the residents think that you're bad in the OR and that you just don't have the technical skills.” (P14) | |

| Cultural accelerants or deterrents | Transparency | Providing information, reasoning, and rationale | “Surgical staff are a little bit more forthcoming in terms of how residents are doing than our attendings. . . they usually do a fairly good job of giving honest feedback, but also giving you a general sense of how you're doing compared to others . . . Feedback is a lot harder to come by from attendings.” (P25) |

| Camaraderie | Feeling of connectedness | “I did a case with [an attending]. There were some frustrating parts . . . one of my senior residents afterwards text[ed] me, ‘Oh, how bad was that? . . . Everyone hates operating with her.’ . . . He must trust me or must see me as a friend, because he's willing to share this gossip with me and is willing to let me in [on the gossip]. It made me feel like I had a bond with him.” (P27) | |

| Competition | Feelings of competition (me versus them) | “[Gossip] can be particularly pernicious [about] the skill set of other folks that are at your level, which I think is normal and natural. But it comes with a bit of an additional edge sometimes, because you feel so dependent on their success for your success, and likewise for the patient's success.” (P20) | |

| Burnout/high workload | External pressures cause prolonged feelings of negativity | “I was feeling negative about the situation. I was frustrated that I'm still there at 11:30pm to do it when I could be home sleeping. So I wanted some way to offload that frustration or those negative feelings. [Gossip] makes it feel better.” (P27) | |

| Mindfulness/self-reflection | Internal reflections or awareness | “There's so many confounding variables about residency that people who are not residents don't understand. My heart breaks a little bit whenever people say anything bad about a resident, because I'm sure there's something else at play.” (P8) | |

| Hierarchy | Power differentials | “It's one thing, I think, for somebody who's your peer to share things with you. I think it's something entirely different when somebody who's in a position of power shares something like that with you, especially something that the resident I'm sure told [this attending] in [confidence]. [This] made me think twice about sharing things with that [attending].” (P11) | |

| Emotions connected to gossip | Guilt | Feeling guilty about participating in gossip | “[Co-residents] go through the list of residents and talk about their clinical performance with me. It's interesting to compare myself to the reputation of other people's, [but] that's where I start to feel like the gossip’s a little bit icky . . . I leave the conversations feeling like maybe I shouldn't have done that.” (P13) |

| Defensive | Defending/rationalizing participation in gossip | “[I’m] someone who tries her best not to gossip in my definition. It's incredibly important to get perspective from multiple people about an individual . . . so that you can better understand which individuals need help and how to improve a program. [Is] it gossip? Yes, because those individuals were not present. But it [is probably] helpful in that situation.” (P33) | |

| Fear/worry | Fear or worry as a trigger for gossip | “I remember feeling concerned for the resident that was involved in the case . . . about how they were taking the whole incident and wanting to reach out and provide support.” (P30) |

Table 2:

| Characteristic | Frequency (%), N=36 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 11 (31%) | |

| Female | 25 (69%) | |

| Race | White | 26 (72%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 9 (25%) | |

| Multi-racial | 1 (3%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic/Latinx | 29 (81%) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 7 (19%) | |

| Post-graduate year (PGY) | ||

| 1 | 3 (8%) | |

| 2 | 2 (6%) | |

| 3 | 11 (31%) | |

| 4 | 19 (53%) | |

| 5 | 1 (3%) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 20 (56%) | |

| Married | 16 (44%) | |

| Intended subspecialty | ||

| Undecided | 6 (17%) | |

| Colorectal | 5 (14%) | |

| Cardiothoracic | 5 (14%) | |

| Surgical oncology/breast | 5 (14%) | |

| Minimally invasive/bariatrics | 4 (11%) | |

| Transplant | 3 (8%) | |

| Pediatric surgery | 3 (8%) | |

| General surgery | 2 (6%) | |

| Trauma/acute care surgery | 1 (3%) | |

| Vascular | 1 (3%) | |

| Endocrine | 1 (3%) |

Appendix A

Appendix B